One of the things I like most about teaching probability is that I still encounter situations that I have to puzzle out. Of course, I enjoy that type of thing but I also appreciate having a genuine opportunity to model to the students how I muddle through a new concept.

One of the things I like most about teaching probability is that I still encounter situations that I have to puzzle out. Of course, I enjoy that type of thing but I also appreciate having a genuine opportunity to model to the students how I muddle through a new concept.

We were recently working on a tile pull "game" in which students had one blue tile and two red tiles. They were to pull out two tiles at once and record if they got a "match" or "no match." After collecting their data, they wrote about whether the game was fair or not. One student asked if he and his partner could double the quantity if they kept the same ratio. "Would that change things?" (A great example, by the way, of the Habit of Mind "Posing problems and asking questions.") I stopped, "Hmm…let me think…" Honestly, my gut instinct was that it wouldn't affect the situation since the ratio 1:2 would be maintained. In the pause while I bit my lip and thought hands began to go up. One student stated emphatically, "It WOULD make a difference because, you see, there's a new way to make a match because now there are two blues. It would change things."

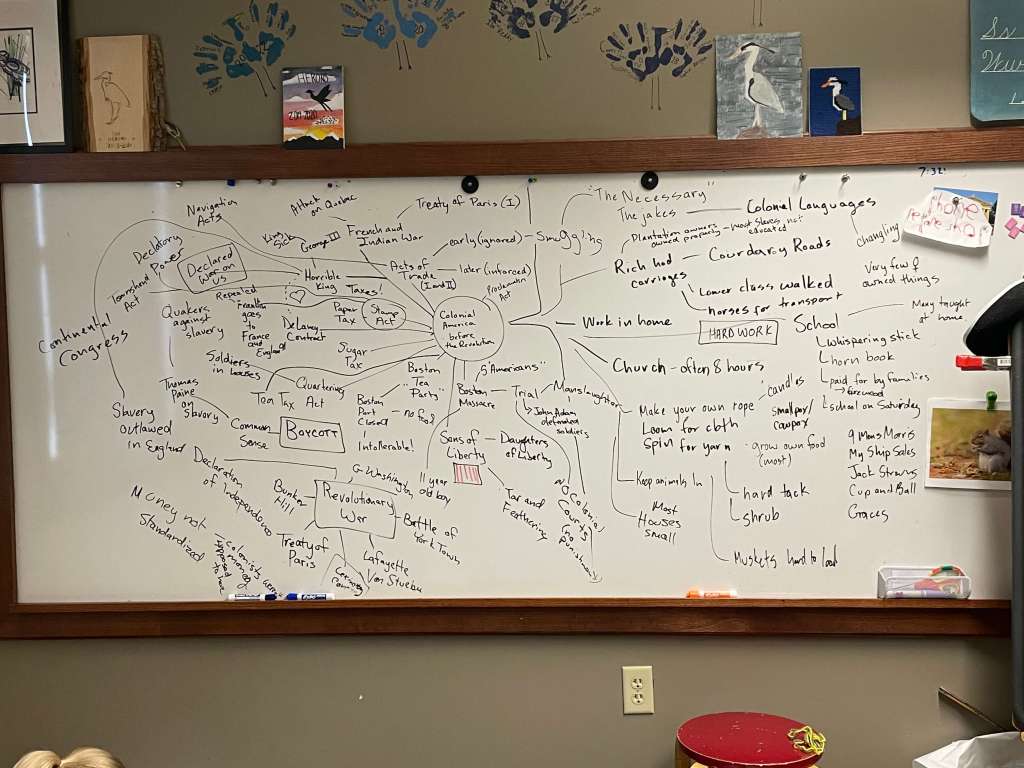

We all agreed that this made some sense but we still wanted to see what would happen. While the students were working on their data recording, I drew all of the possible pulls from the first set up and the doubled set up. One out of three pulls is a match when you have two of one color and one of another. When you double the tiles, there are seven out of fifteen matches. I shared my chart with the class (for some of them, it was simply an exposure to that way of divining probability, for others it was instructional) and we compared my predictions to the data they had collected.

In probability, our first instinct is often wrong. That's why we teach that using math and numbers to help us make better predictions is so important. The above activity went on to look at two other situations, one in which there were two blue and two red and one in which there was one blue and three red. Initially, all of the students felt that the two red and two blue would produce the fairest game in terms of matches. They were shocked when their data pointed clearly to the third game as the fairest.

What was going on? Once we drew out the possible pulls a collective, "Oh!" escaped from the class. There are six possible pulls in the final game — 3 matches and 3 no matches. Math triumphed — they were convinced.

Leave a comment