Special Persons' Day has a fragmented schedule. Students are either performing or serving or giving tours (or giddiliy anticipating one of those things). Visitors drift in and out. It's wonderful but it is not usually a day when we do our highest caliber intellectual work.

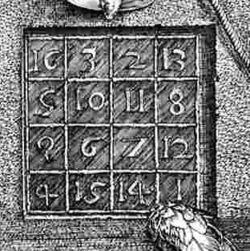

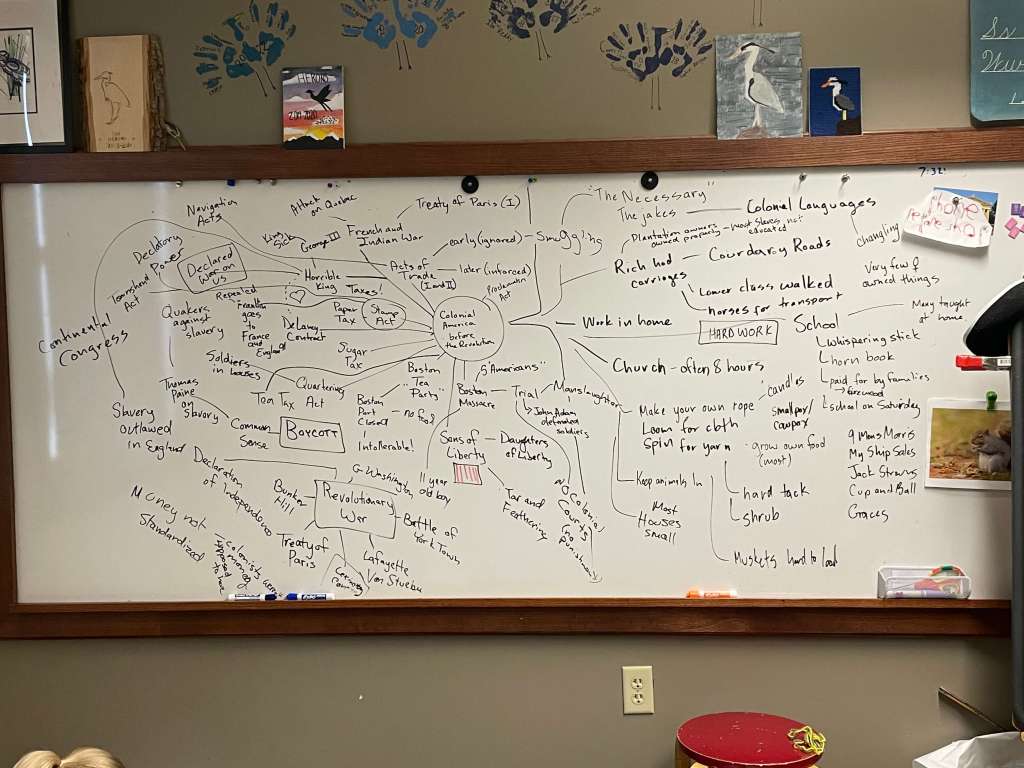

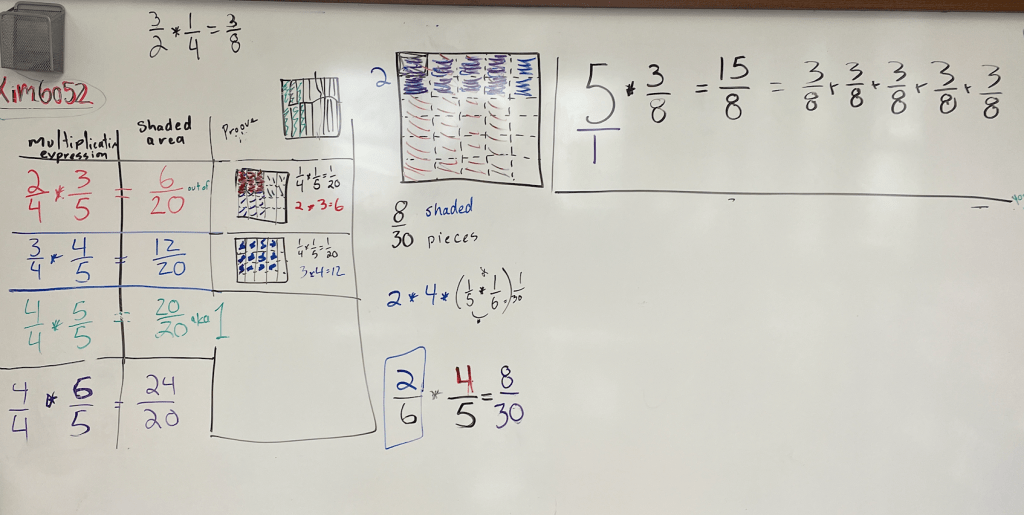

Not so today. I had planned a simple lesson on magic squares – a mathematical amusement that first appeared in India around the time that we are studying in our theme. A square grid is filled with consecutive numbers so that each row, column and diagonal equal the same sum, the "magic number." My plan was for students to puzzle out the squares and join me if they got finished to learn a method of creating the squares from scratch.

Our introduction tipped me off that the Herons were hungry for a little more today. As part of the lesson, I talked about the Base 10 system that emerged from several cultures along the Silk Road and compared it with the Roman numerals we are using in Charlemagne's court. One Heron asked about other bases. "Show them base 12!" he said. The Herons were game and started to play with the idea of having more than 9 symbols as digits. "I'm A years old!" "I'm B!" (That's how you represent the quantities ten and eleven in Base 12) Another student raised her hand to ask, "How would you do Base…37?" She was thinking ahead to running out of letter symbols.

I tucked away the reminder to teach bases soon and returned to the planned lesson but the Herons' math curiosity was stoked. They hurried off to work on filling in the grids and were soon explaining their various methods for figuring out where numbers went. Many started with sheer guesswork but then began to apply logic and strategies.

After filling out the first two, kids realized that the magic number for both was 15. Was this always the case? I gave them some more examples. All of them were 15. "Why?!" They started to see that certain pairs of numbers went together. But was it always 15? Several students added all of the digits 1-9 together and got 45 — 3 groups of 15. There were 3 columns! They had discovered that in order to work, the sum had to be the average.

There were yelps of excitement as they figured this out and then they scrambled back to their tables. Could they use the same method to discover the magic number for a 4×4 grid? They added furiously. One student was disappointed because it didn't work – she got a fraction. But a friend pointed out she had divided by 3, not 4. "Oh! It works!" They used their prediction to fill in a 4×4. This time with squeals of excitement.

I jettisoned my original extension plan to create our own squares in favor of the authentic thinking work that was going on. I circulated students and asked them questions to push them a little further, make another connection, challenge an assumption. Their were groans when I announced recess, "Just a second!" There is nothing more powerful than the sense of discovery, not even recess.

Leave a comment