Our Valentine's celebration on Friday was a lot of fun as always. We passed out our valentines in the morning. We sang a song or two about love. We filled in our Love Bingo charts with the messages from our conversation hearts. We sent first winners of Love Bingo down the tunnel of love (the staff lines up to give hugs) Students were told not to clear their boards. We pulled a fifth heart and read its message… about five groups yelled "Bingo!" We gave them hugs and pulled a sixth heart…almost the entire gym erupted, "BINGO!" The line for hugs snaked around the gym. An unprecedented number of Love Bingo Winners. It was crazy. It didn't make sense. This had never happened before. I sniffed a math lesson. Being able to use math to solve a real world mystery is an opportunity I couldn't pass up.

Our Valentine's celebration on Friday was a lot of fun as always. We passed out our valentines in the morning. We sang a song or two about love. We filled in our Love Bingo charts with the messages from our conversation hearts. We sent first winners of Love Bingo down the tunnel of love (the staff lines up to give hugs) Students were told not to clear their boards. We pulled a fifth heart and read its message… about five groups yelled "Bingo!" We gave them hugs and pulled a sixth heart…almost the entire gym erupted, "BINGO!" The line for hugs snaked around the gym. An unprecedented number of Love Bingo Winners. It was crazy. It didn't make sense. This had never happened before. I sniffed a math lesson. Being able to use math to solve a real world mystery is an opportunity I couldn't pass up.

That afternoon, the Herons secured the crate with the love bingo materials. We had the evidence — we could figure out the mystery. We began with a few questions: What had happened? What are some reasons it might have happened? How could we figure out what happened? How could we change the game to make it better next year?

The answer to the first question came quickly – more people got bingo a lot faster this year. Almost everyone had won in just six or seven pulls (we play on a 4×4 board).

The Herons had great ideas for why this had happened: The game was rigged. People cheated. There was a lot of confusion and people thought they were supposed to go up whether they had won or not. People covered multiple squares when a heart phrase had only been called once. We didn't clear the cards like we had in the past. And finally, there were a lot fewer heart messages than in the past. There was general agreement on the last statement but students weren't sure how that would affect the game.

We decided to collect data on our conversation hearts. Each child took a bag of 16 hearts that had been used to set up a bingo card and tallied the phrases they found. It turned out that there were only six phrases and that they all appeared about the same amount of time except for one ('Hugs and Kisses") which only appeared about half as much as the others. While we didn't have a bag of our typical brand of candy hearts to compare, students recalled messages such as "text me" and "UR Cute" that weren't among the phrases on these hearts (which were foam hearts meant for craft projects.) What did it mean?

We decided to collect data on our conversation hearts. Each child took a bag of 16 hearts that had been used to set up a bingo card and tallied the phrases they found. It turned out that there were only six phrases and that they all appeared about the same amount of time except for one ('Hugs and Kisses") which only appeared about half as much as the others. While we didn't have a bag of our typical brand of candy hearts to compare, students recalled messages such as "text me" and "UR Cute" that weren't among the phrases on these hearts (which were foam hearts meant for craft projects.) What did it mean?

One student reminded everyone that he thought the bag of hearts the caller used might have been rigged. We dug it out and counted its contents – the proportions matched the other bags. "Not rigged." he concluded.

Other students shared anecdotes of students being confused and possibly erasing their original placements in order to win. How could we rule that out? Amy Narveson suggested that we run an experimental round of bingo without cheating or confusion to see if our results matched what happened in the morning. We handed out the bingo sheets from the party and began.

Sigh – experimental probability being what it is, I pulled three "Hugs and Kisses" in a row for pulls four, five and six. Many students who had three in a row after three pulls stalled. The seventh pull had us back on the statistically probable tract — one winner. The next pull — four winners. The next pull after that — over half the class. Our results almost matched what happened in the morning (except for the three unlikely pulls.) Cheating and confusions were not big players in what happened, although they may have contributed.

At this point, many students concluded that not clearing the board between winners had been the main cause of the huge number of bingos. They were right. We looked at the probability involved by playing a game with a board I'd labeled with the numbers 1-6 to represent the six phrases. We rolled a die to determine what we could mark out. I used a die on purpose — it is a familiar tool in our study of probability and students were able to quickly understand that if there were 4 numbers in a row, I had a 4 in 6 chance of rolling one of those numbers. The connection would have been a little more tenuous if I had just used conversation hearts; this brought it into focus.

Sure enough, we saw that it was very hard not to win once six or seven phrases were called. Comments included, "Woah, you mark something off every time – you always have what's called." "We can win three different ways so there's a 3/6 chance we'll win with the next call." "That's a one half chance!"

Students concluded that at the very least we should clear cards between winners next year. Many wanted to use candy hearts again to get more phrases so that you didn't always have a phrase that was called. Several wanted us to be more clear with the instructions so that we could rule out confusion.

A few students still thought cheating had happened. I've always found that even in the face of overwhelming mathematical proof, some kids will hang on to anecdotal beliefs ("Yes, I know the chances of rolling a two are 1 in 6 but I always roll twos.") It is, perhaps, human nature to do so (consider the lottery.)

But, for the majority of students, collecting data, running an experiment, and using probability helped them to analyze a situation and make some great suggestions to make the game better next year.

Thank you for reading almost a thousand words about Love Bingo. I thought it would be a valuable snapshot of how progressive mathematics can work. We had an authentic situation that could be understood with numbers. The students were able to apply their data and probability experience to a real problem. Had they not had the previous experience, they would not have had the tools they needed to reach a satisfying solution. Their knowledge had a purpose.

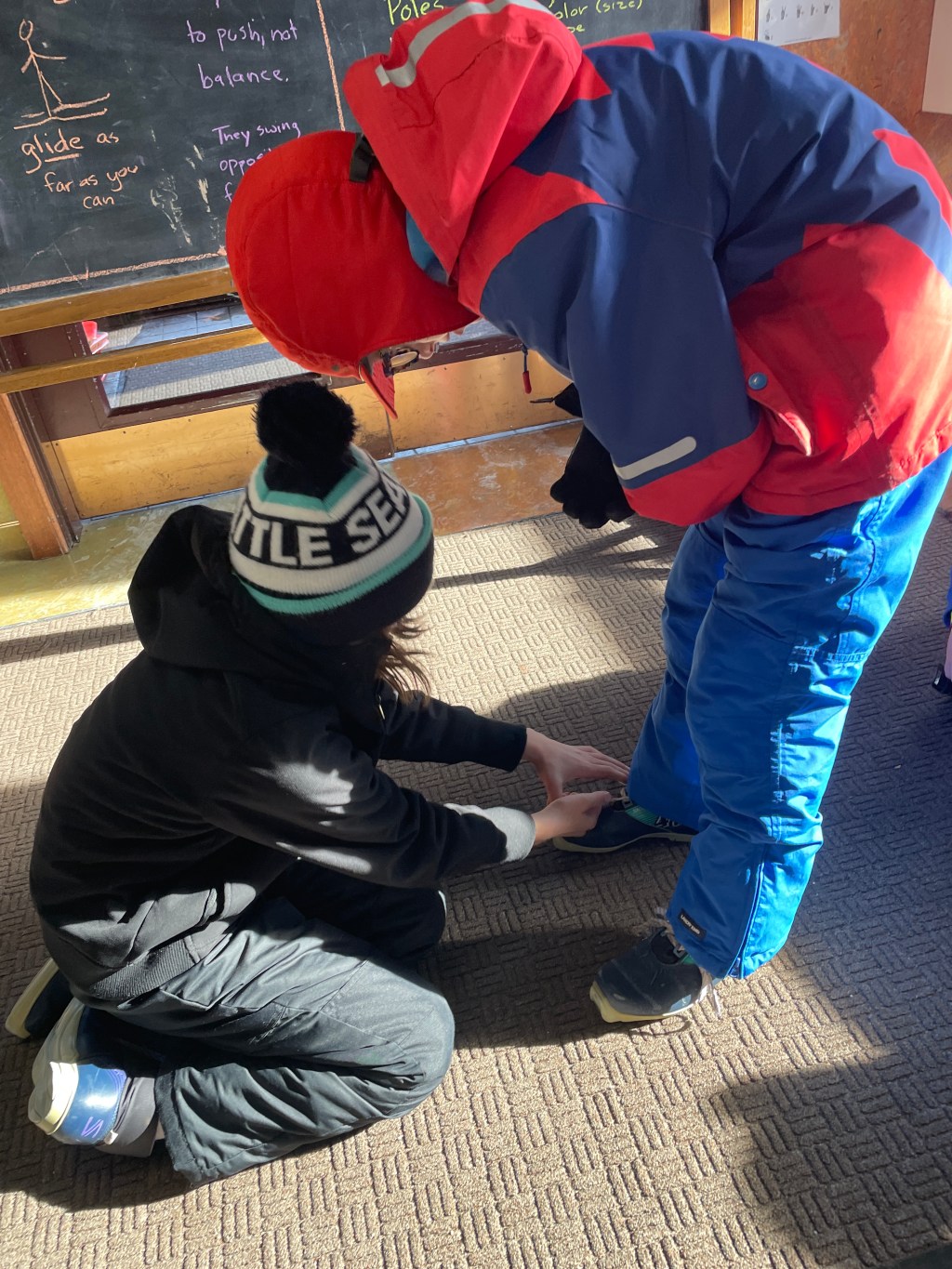

And now for something completely different — very goofy pictures of the Herons. Sorry for the even shakier than usual video; I was hugging with one arm and shooting video with the other.:

Leave a comment