This past week, in conjunction with the work of the Flying Foot Forum, we did a mini-theme on the puzzles and mathematics of Lewis Carroll. Carroll was a mathematician at Oxford and loved puzzles. He had insomnia and would often spend his sleepless nights thinking about various enigmas (which he published in a book called "Pillow Problems") Many of these puzzles are very complex but he also created simpler puzzles to amuse and challenge the children in his life.

We began the theme by reading from a letter he wrote to a young acquaintance. In it he posed a problem but also shared this story:

I must tell you an awful story of my trying to set a puzzle to a little girl the other day. It was at a dinner party, at dessert. I had never seen her before, but, as she was sitting next me, I rashly proposed to her to try the puzzle (I daresay you know it) of "the fox, the goose, and bag of corn." And I got some biscuits to represent the fox and the other things. Her mother was sitting on the other side, and said, "Now mind you take pains, my dear, and do it right!" The consequences were awful! She shrieked out, "I can't do it! I can't do it! Oh, Mamma! Mamma!" threw herself into her mother's lap, and went off into a fit of sobbing which lasted several minutes. That was a lesson to me about trying children with puzzles. I do hope the square window won't produce any awful effect on you!

The 4/5s saw the point of the story right away. There is no way to "do it right" when it comes to approaching a puzzle. One has to be willing to try out different approaches, many of which will be fruitless. If one believes there is only a single pathway and you must find it first, one will be unable to start. How does one find that pathway from the myriad options one has as one begins to pick apart a puzzle?

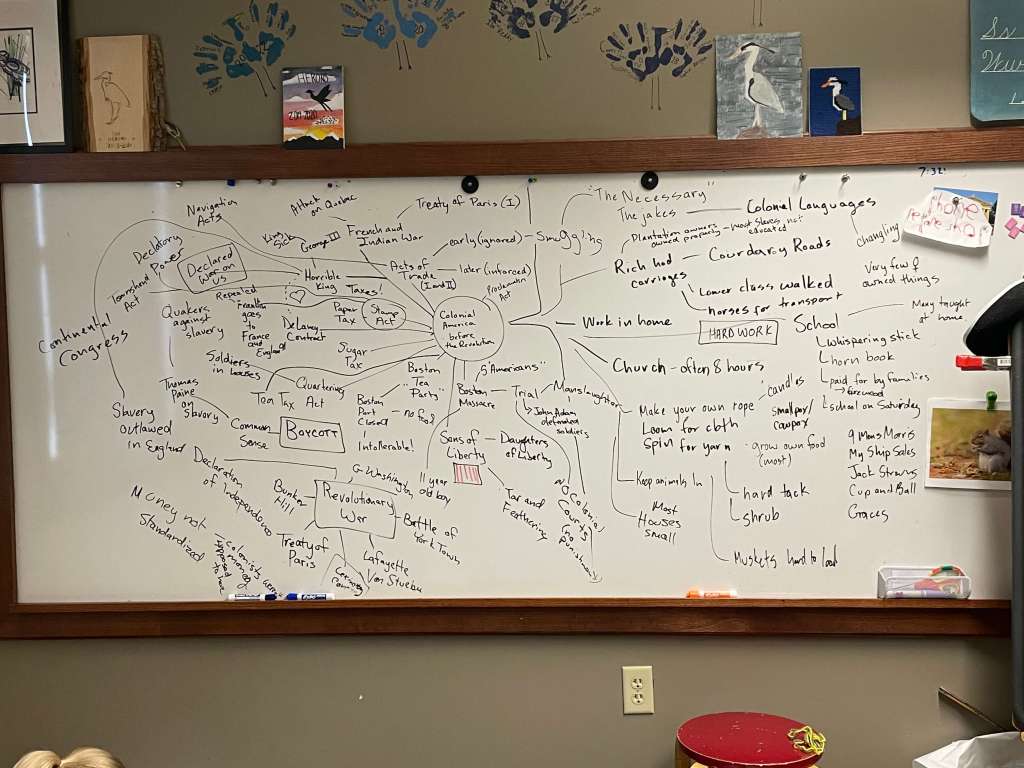

We tackled cake problems, syllogisms, doublets, mazes, network puzzles, river puzzles, the alphabet code and the captive queen. We also explored Carroll's method for dividing by 9 and 11 that involved no dividing — just subtraction and adding. Here the puzzle (unsolved by us so far) was not the algorithm (which is a lot of fun) but determining just why it works and, at a deeper level, how Carroll discovered it in the first place. Similarly, Carroll's algorithm for determining the day of the week for any date in history works beautifully but its mechanism remains a mystery to us (although not to professional mathematicians).

Many of the students were intrigued by someone who could create puzzles and ideas like this. How did he figure all of this out? Why? Of course, as a tutor at Oxford, he had a classical education with a very strong arithmetic focus. He was an expert in geometry, algebra, symbolic logic and calculus. But he was also incredibly imaginative and playful. These puzzles and algorithms are accessible representations of some very complex concepts in mathematics. About half way through the week, the students began to talk about how Carroll was "playing" and having fun with the math.

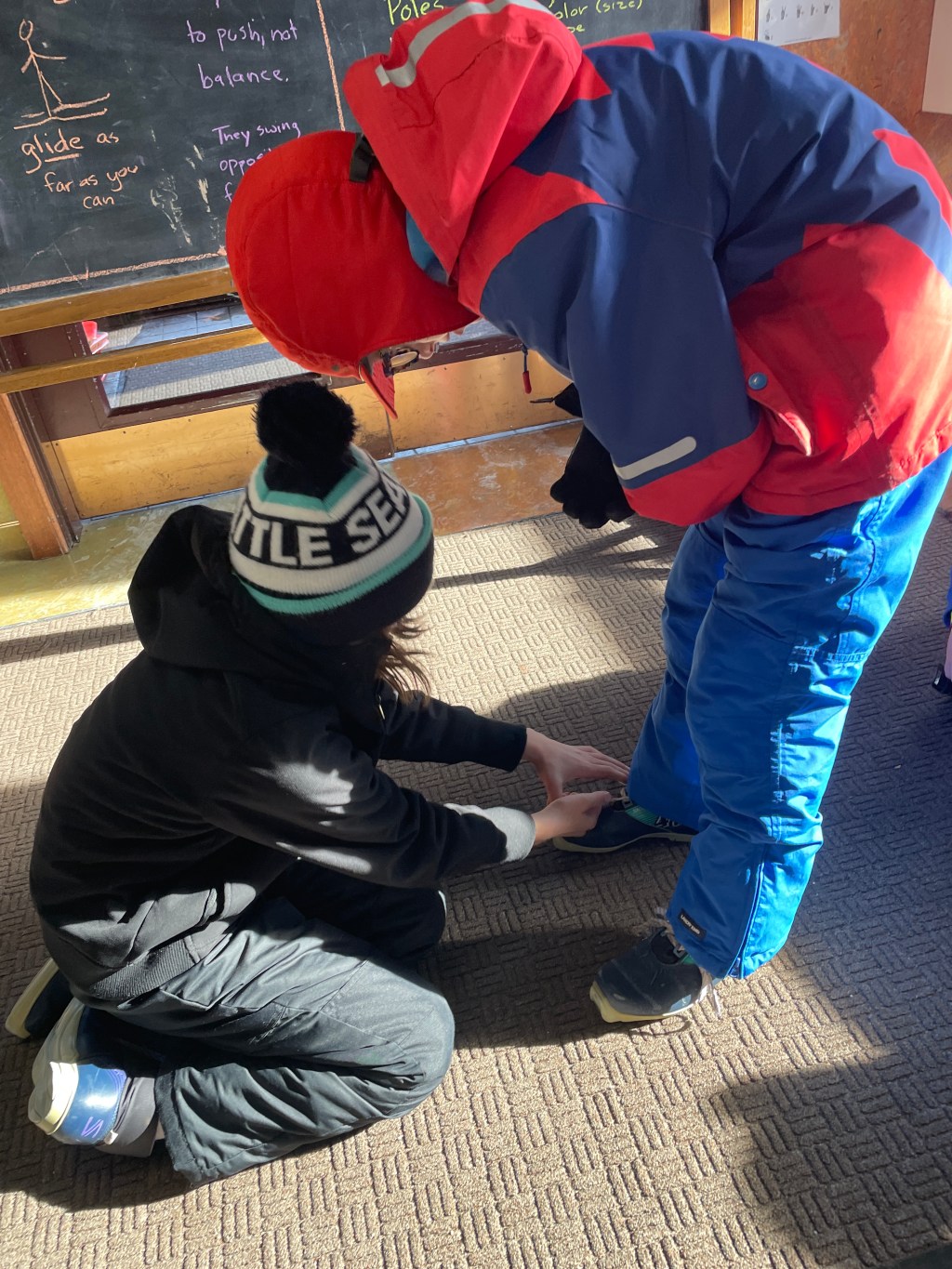

The notion of play and discovery is central, of course, to the work in a progressive classroom. Often, when we talk about "play" people think of doll houses and blocks. But, as children get older, play takes on a more intellectual form. We play with ideas. We mess with our brains. The fun is in the utter confusion and frustration of not getting something.

It was a joy to watch the Herons puzzle and wonder and, at times, scream with frustration only to experience the joy of discovery a few minutes later. Luckily, no one ended up sobbing in my lap.

Leave a comment