This summer we found a tiny monarch caterpillar on some milkweed by my folks’ house in Indiana. It was maybe a centimeter long and, at first, it seemed like it wasn’t eating anything. Then we noticed a tiny trail of holes in the leaf. Soon the trail and the caterpillar were bigger. There seemed to be pattern of a lot of eating followed by little eating. One morning I woke up to find the caterpillar squeezing itself from end to end. The caterpillar jumped in size as I watched – literally bursting out of its old skin.

This summer we found a tiny monarch caterpillar on some milkweed by my folks’ house in Indiana. It was maybe a centimeter long and, at first, it seemed like it wasn’t eating anything. Then we noticed a tiny trail of holes in the leaf. Soon the trail and the caterpillar were bigger. There seemed to be pattern of a lot of eating followed by little eating. One morning I woke up to find the caterpillar squeezing itself from end to end. The caterpillar jumped in size as I watched – literally bursting out of its old skin.

Soon it crawled to the top of the jar and began to shake its head back and forth repeatedly. After several hours, it had suspended itself upside down and curled itself into a “J.” It began to compress from top to bottom again but this time, the yellow and black striped skin of the caterpillar split to reveal a bright green skin. This hardened into a chrysalis, and, as of this writing, that’s where the process remains.

I knew all of the steps of the monarch life cycle but I’d never watched it unfold in real time. I learned so much more when I had the opportunity to see the whole process.

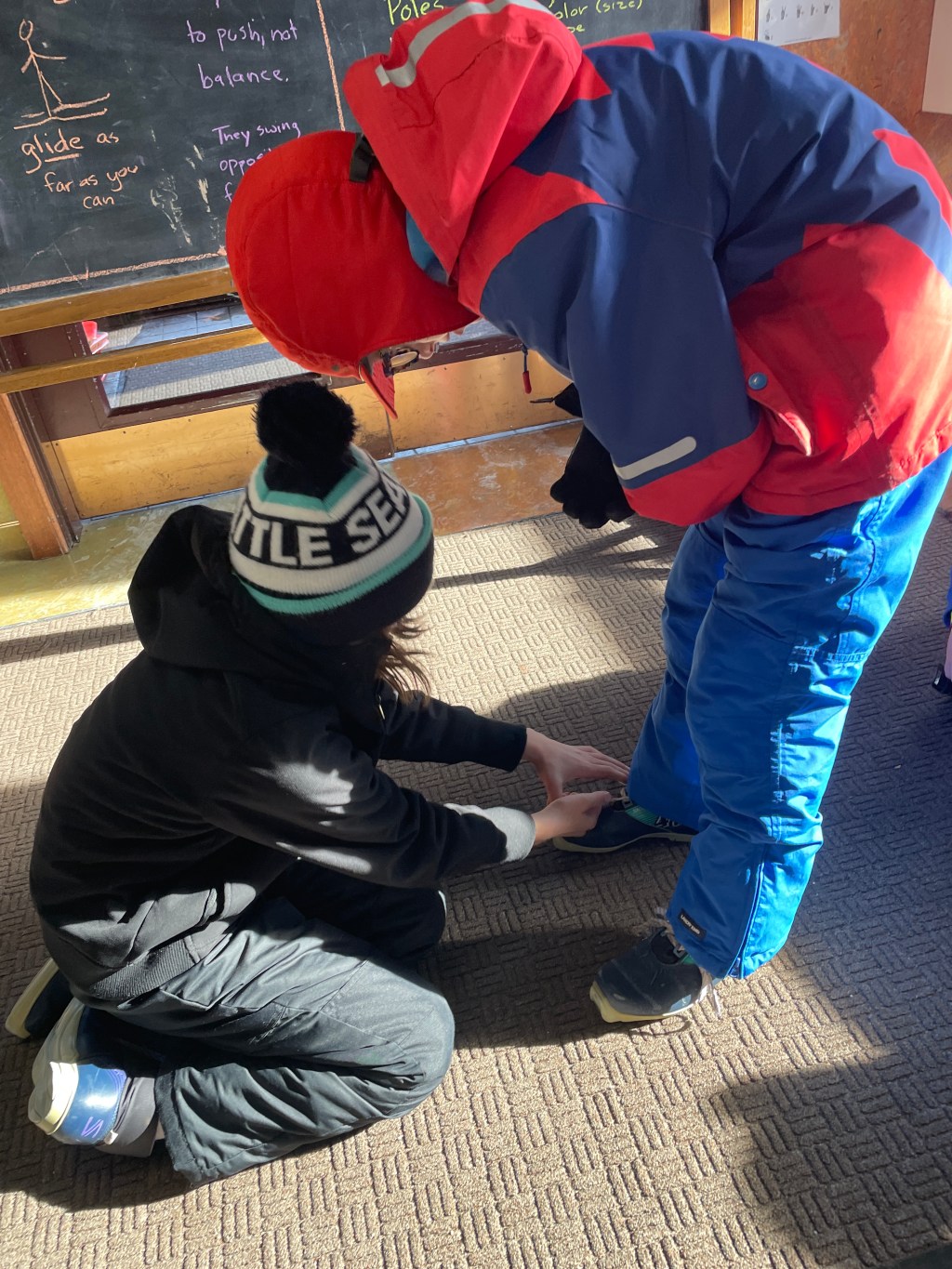

The same is true as your children enter the Herons. Much of my teaching day is spent watching, observing, listening. It’s one thing to have a child answer a problem on a paper – it’s entirely another to watch how he or she arrived at that answer. The response on the paper is binary – yes/no, right/wrong. Observing the process the child uses gives me so much more information. Does she consider several approaches or does she always use the same one? Does she ask for help right away or does she sit and ponder a while? Does she look for connections among problems? Does she check the work she’s done? Does she wonder what would happen if the problem used different numbers? Does she love the feeling of mastering a comfortable problem? Does she enjoy problems only when they are “interesting”?

At reading time: Does a child settle right in or does he wander? Is he confident when choosing a book or does he just pick up something? Does he read fluently? Does he read with affect? Do his eyes stay on the text or does he look up often? Does he have a preferred genre? How does he tackle new words or figurative language? Is he able to summarize what's happening?

At lunch or recess time: Does a child seek out others? Is she sought out? Is her play physical, imaginative, both? Does she have one friend, several, many? Is she able to solve problems? Does she seek out adults for companionship?

These first weeks are structured to give me lots and lots of time to watch, gather information, ask questions, and have conversations. I use some formal assessments such as spelling inventories, structured reading assessments and math assessments. These give me one kind of information efficiently and, because they are assessments we’ve used our expertise to choose, effectively. But they only provide a snapshot – like a poster of that caterpillar’s life cycle with still photos at each stage.

It is my observations that bring the image of the learner to life. I can figure out not just what a student needs to learn next but how he might best learn it. The classroom is not a binary world. Students are wonderfully complex beings. To teach well, we need don’t just need data points – we need a deep understanding of our students, an understanding gleaned only through very careful watching. I am so looking forward to getting to know your child.

Image from: paulmirocha.com

Leave a comment