Sometimes folks ask how we can teach math when we have two different grades in the classroom. They assume that I would have to teach one fourth grade lesson and then a fifth grade lesson. "How can you find time to do math and everything else?"

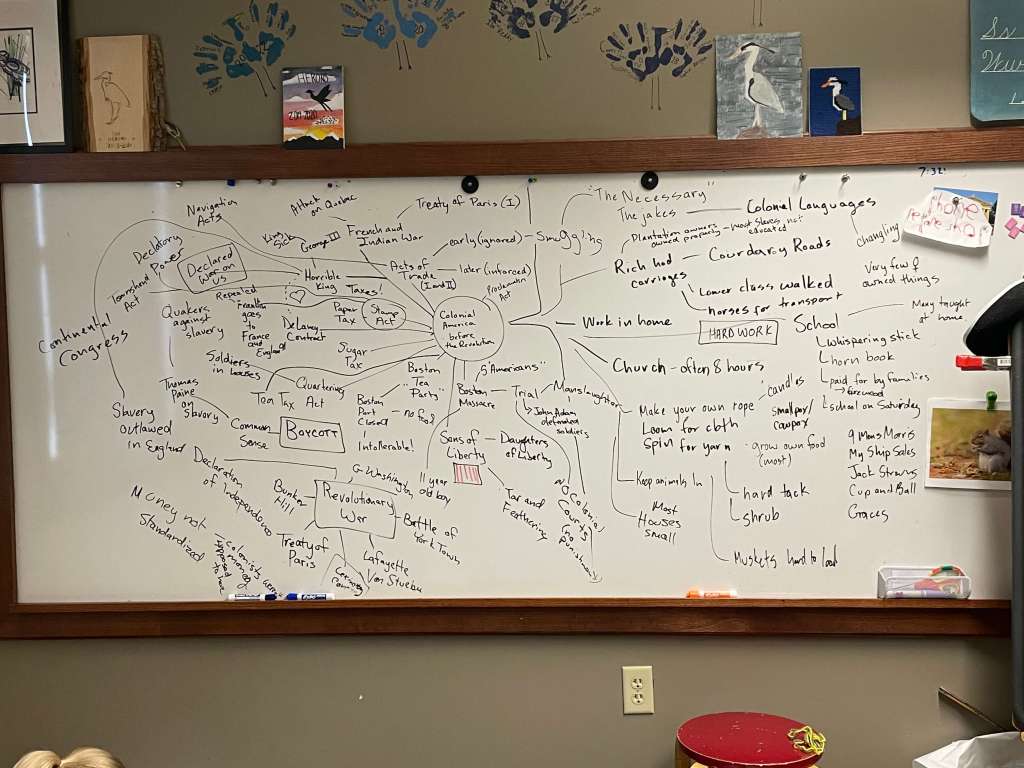

The answer is we design math experiences that allow us to use a common experience to challenge students in a variety of ways. As an example, we on the first day of school I introduced a survey that students would ask the class. We talked about what would make a good question – given that we wanted to display our results in a graph. While "What's the meaning of life" (one Heron responded with confidence "42" – thank you Douglas Adams) might elicit interesting responses, chances are good that you'd get 20 different responses – not something that a graph would help one understand. On the other hand, questions with just a "yes" or "no" answer might also lead to graphs which were not as interesting.

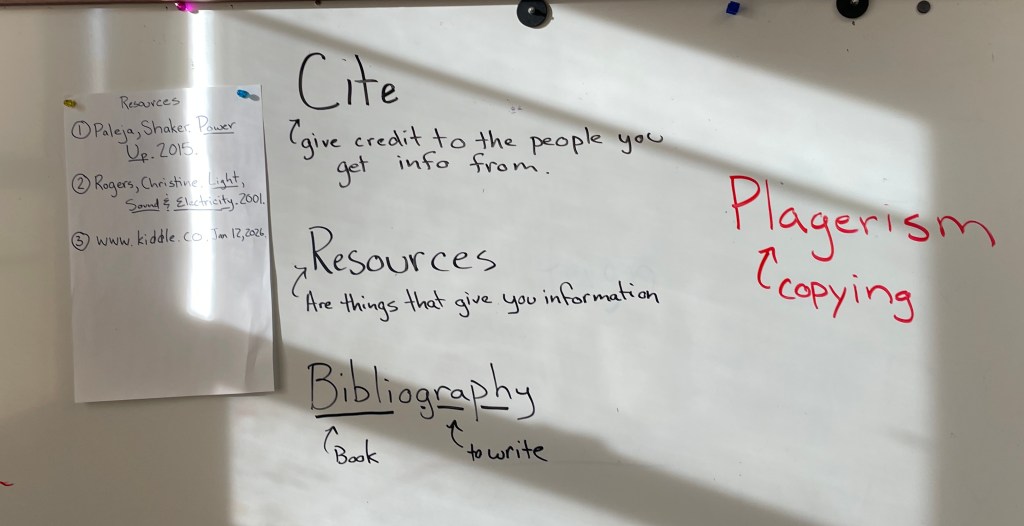

I taught students about "forced choice" questions that help ensure that one's data are not too scattered. Then we talked about two ways to collect raw data: tallies and line plot graphs. Many chose tallies but everyone was exposed to the idea of line plots and some children tried it out (and their peers saw them using this technique).

I taught students about "forced choice" questions that help ensure that one's data are not too scattered. Then we talked about two ways to collect raw data: tallies and line plot graphs. Many chose tallies but everyone was exposed to the idea of line plots and some children tried it out (and their peers saw them using this technique).

Everyone made a pictograph with his or her data. This allowed me to introduce and review some vocabulary such as "title" "axis" "key" and "symbol". It also gave me a chance to do a quick assessment as children worked to use symbols that represented more than a single vote. How did students handle 5 votes if their symbol represented two votes? Were they able to grasp that symbols had to be the same size so that comparisons were easy and accurate?

After completing the pictograph, I asked students to represent their data in another way. For some, this was a bar graph – a good chance to solidify the work we had just done in pictographs. Others were asked to create a circle graph – some used a circle divided into 20ths (most children asked 20 people our question), others used a circle marked with 100 percentage points, others created a circle from scratch and used a percentage protractor to mark out their percentages. Some children had chosen to ask more that 20 people their question in order to have a greater challenge when it came time to work on percentages.

A handful of children finished their second graph and asked, "What next?" We had used a class example of asking how kids were getting home and I suggested that they gather that data for the whole school and see how we compared to the other classes. This group surveyed the school and, working together, figured out the percentages for each class. They also figured out the average for the school so that classes could compare themselves. They shared their work with the class – helping everyone see how percentages allowed us to make useful comparisons among different sized groups.

Whew! Here again the mixed age classroom enables this kind of learning. Many of the fifth graders were exposed to these ideas last year. This year, they were the ones taking the lead on the extensions while this year's 4th graders watched and, in some cases, joined in. Some fifth graders also explained pieces of the assignments to the 4th graders and supported them both formally and informally.

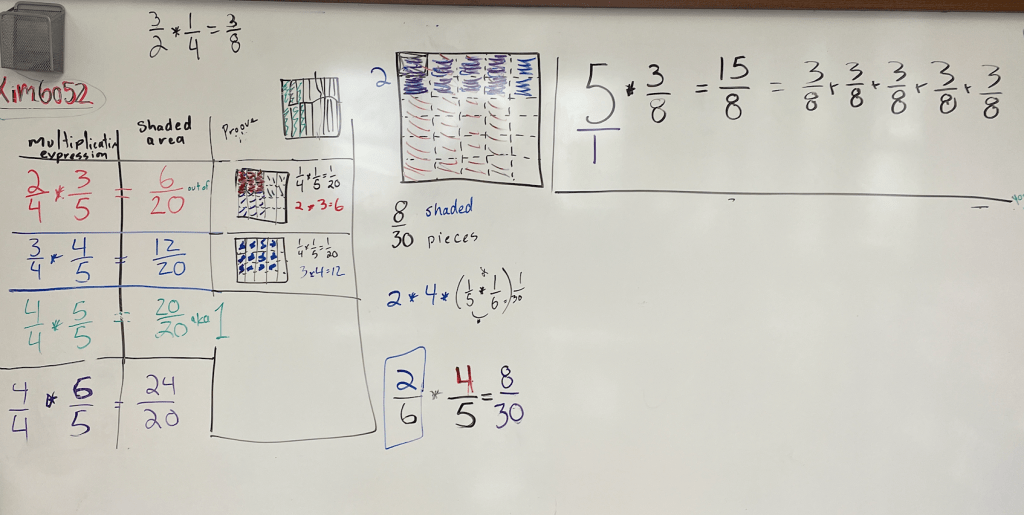

So that's one example of what math looks like in a mixed grade, progressive classroom. I wanted to share an example as fodder for our discussion at curriculum night on Tuesday. Here are images from the display the students put up by the library (for the whole school to be able to use.)

Leave a comment