Seven years ago I taught the series of pentomino lessons that I am currently teaching during exploration math. It's a great series of lessons and it was created by Sara Currier, my co-teacher at the time. We define what an -ominoe is (a series of tiles on a plane that share at least one entire edge.) Then we figure out how many triominos, tetrominoes and pentominoes exist. We identify which are nets for open cubes (a net is a flattened out version of the three dimensional shape). On the last day, we take milk cartons and the students work together to decide where to cut to create the eight pentominoes that are nets of open cubes.

Seven years ago I taught the series of pentomino lessons that I am currently teaching during exploration math. It's a great series of lessons and it was created by Sara Currier, my co-teacher at the time. We define what an -ominoe is (a series of tiles on a plane that share at least one entire edge.) Then we figure out how many triominos, tetrominoes and pentominoes exist. We identify which are nets for open cubes (a net is a flattened out version of the three dimensional shape). On the last day, we take milk cartons and the students work together to decide where to cut to create the eight pentominoes that are nets of open cubes.

When I co-taught the lesson seven years ago, we had a lot of fun and the students did some great exploring. But I have been struck by how differently I am teaching this lesson now. We have done so much professional development in the area of math — the rhythm of my teaching is different and what I teach is different, too, even in "identical" lessons.

So this year, I am doing exactly the same lessons — but on the first day, I put up an incomplete definition of an -ominoe: "square tiles that share a side". As we explored together, we tightened up our definition to "square tiles on a flat surface that share at lest one entire edge." Each of the changes were made when students asked questions about what "counted." As these questions came forward, I emphasized that questioning was a key mathematical habit of mind and that using precise language was also important in math – we all have to be on the same page.

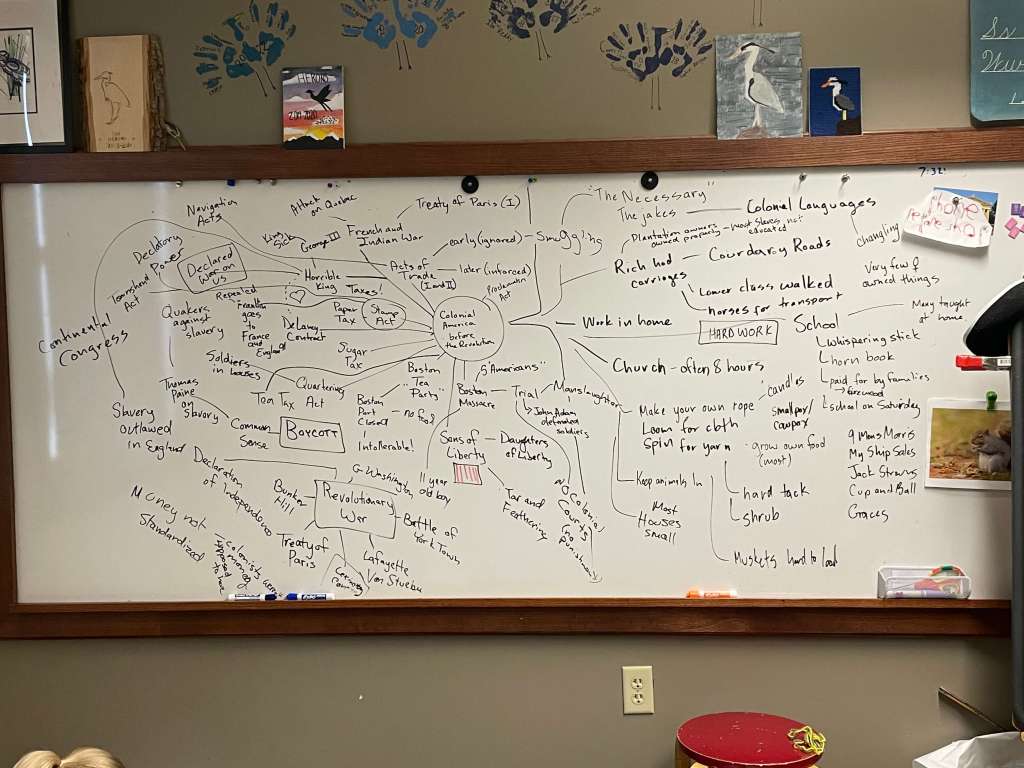

As students found the number of triominoes and tetrominoes, I created a table on the board. I pointed out that mathematicians work in an organized way so they can understand their work later and so that they can explain their work to others. It also helps them find patterns.

Several students spontaneously tried to use the table to predict how many pentominoes there would be. Instead of just nodding and saying "let's see!" I pointed out that mathematicians try to extend patterns and they make predictions.

When the students announced that there were twelve possible pentominoes (they had already determined together that reflections and rotations count as a single pentomino) I pushed them to explain how they knew they had them all. We agreed that it was likely since we all had the same number but that it wasn't completely convincing. "Mathematicians try to prove things so they are known without a doubt…how could we prove it?" One student explained her approach — she took each tetramino shape and shifted a fifth tile around all of the positions to see what new shapes it made. We tried it and found all twelve pentominoes and, importantly, realized there couldn't be any more because we had tired all of the possibilities. We had used a systematic approach instead of guessing and checking. When I first taught this lesson, I was the arbiter of truth. "Yes, you found them all!" or "Nope, keep looking." By putting the onus on the students to prove there were twelve, our conversation was richer and, importantly, they were doing the work of real mathematicians, something I could point out to them.

As the lesson proceeded, I pointed out strategies students were using and connected them to the mathematical habits of mind. In math, a hypothesis is called a conjecture. When one student said, "Woah…maybe you can make every pentomino [from a milk carton] by making four cuts…" I asked what the other students thought. Many were unsure but it was something they paid attention to as they worked. I called it what it was, "a conjecture" and asked students to find evidence for or against it as they worked. We were doing the real work of mathematicians – proving and disproving patterns. Seven years ago I would have said, "COOL! I don't know…let's find out."

This lesson has always been a good one – engaging and creative. But now, it's more. It helps students recognize patterns in their own work that they can then take into their other math work. These mathematical habits of mind (similar but more specific than our regular habits of mind) have come to the forefront of our math teaching. It's exciting to see the difference seven years make.

Leave a comment