This summer I am taking a class in number theory. Number theory is defined as the study of integers (whole numbers) but is also a lot about how numbers work. It's something I knew of and had played with a little but it didn't go much deeper than that.

As adults, most of us very rarely do something that is completely new to us. We spend our lives in the comfort of competence. And yet, our children are asked to spend large swaths of their day learning brand new things. It's hard, hard work. (A few years ago, some of the other teachers and I took a class on spoon making that lead to a lot of reflection on the work of learning — I had a chance to write about the experience; you can read the blog entry here.) Taking this math class was a reminder of what I'm asking the Herons to do every day.

The experience has been very frustrating at times and often very humbling. There have been some problems that I've puzzled over for days. Paragraphs that I have had to read and read again and then read out loud to start to make sense of. Last night, my husband glanced nervously up the stairs toward the kids' bedrooms when I let out a whoop of victory at 11pm, having just seen a path to a solution that had seemed impossible.

The Slippery Nature of Learning

So many times when I was reading a new chapter or working on a set of problems, I would get into the swing of things. I would get a couple right in a row without struggling. I'd congratulate myself, go get a cup of coffee and when I came back…the thing that I had just been able to do was unfamiliar again. I'd have to go back to my previous work and piece together what I had been doing. It was almost more frustrating than not getting it at all – and yet it is so common when we are learning something new.

Eventually as I moved through the problem sets, I would be able to hold on to the procedure and execute it correctly. But then there was another hurdle…I would come across a problem and wonder, "What does this have to do with what we were doing?" Because these are well constructed problem sets, I as an adult learner knew that I was missing something (although the temptation was still strong to say, "This book is stupid.") Inevitably, what I was missing was knowing how and why the procedure worked. When I pushed myself (and it took a lot of pushing) to really understand what was going on and why it was a valid way to reach an answer, I found that I was able to recognize the math more easily in new contexts. Those "completely random" problems turned out to be completely related; it was just a new context.

But even then, I wasn't done. I could use the math effectively, but I wasn't yet inventive and creative with it. And I wasn't yet using it to make sense of new ideas I came across. That took even more work.

Owning It vs. Getting It

A friend shared that she could feel the difference when a concept moved from something she "got" to something she "owned". The "getting" can often come quickly. Something is confusing…someone explains it well…and then it makes sense. Way too often, that's where learning stops. We become complacent as soon as the piece falls into place, its rough edges smoothed. But, to continue the metaphor, we often don't stay with the piece long enough to see how it fits with the wider picture.

To truly and deeply understand something we have to poke it and prod it. We have to see what it does in new settings. We have to break it and put it back together. We have to stay with it long after we've "got it". Owning a concept takes time and it takes practice. And it's only after we own a concept that we can truly use it. It pops out to us when we're looking for a way to solve a problem. Its connections to other concepts are apparent. You can use it to make sense of new ideas (and eventually own them, too.) And it sticks — you can't forget it because, well, it just makes so much sense. You are no longer working to remember it because it's self evident.

Translating to the Classroom

So…why did I spend a lot of my summer learning math that is only tangentially connected to what I teach in the fourth and fifth grade classroom? I've found that to be an empathetic teacher, I have to be reminded (often) of what it's like to not be able to connect the dots. When a student says often for the fourth or fifth time, "This makes no sense…" I need to be able to nod and say, "I know how you feel…let's pick it apart and find something that makes a little sense and go from there."

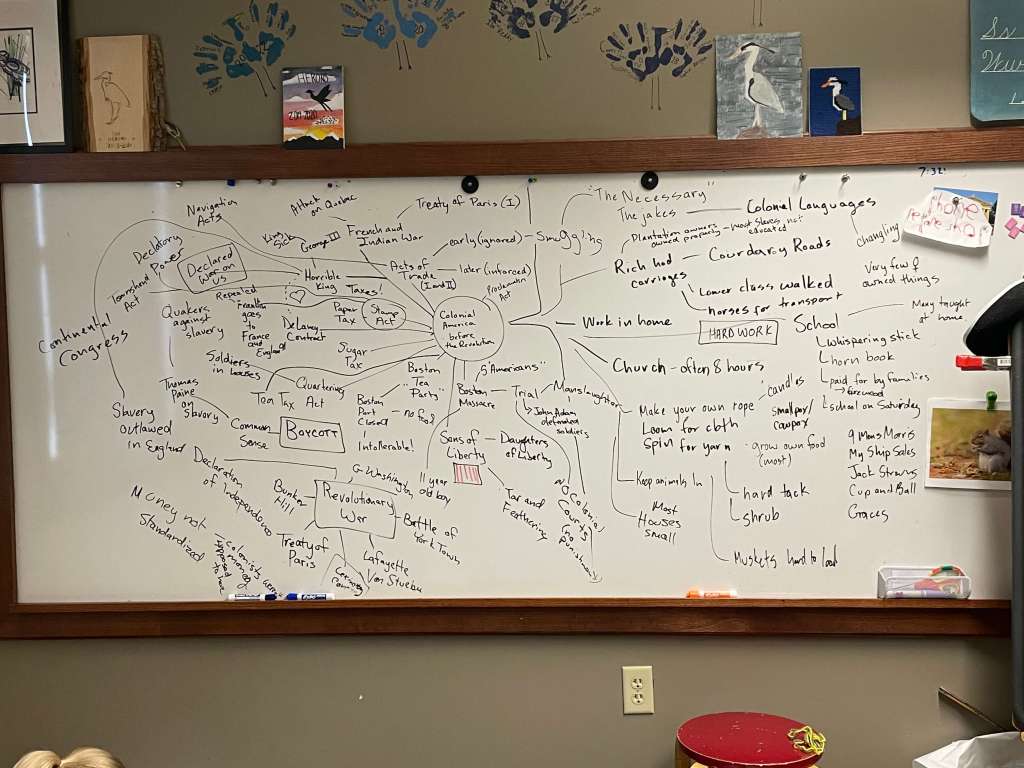

But beyond empathy, this math experience has highlighted for me the importance of the mathematical habits of mind that we use in class. Learning mathematics is so much more than doing math problems. You have to expect math ideas to make sense…eventually. You have to look for patterns. You have to make hypotheses (conjectures) about how the math works and then test those ideas to see if you're right (or how you could change them.) You have to make models – draw pictures, number lines, tables – to make sense of things. You have to challenge stopping when you get a right answer and push yourself to understand how you got the answer and why it worked.

I had to do all of that this summer – and I am so excited to continue that work in the classroom.

Leave a comment