We are in the midst of a geometry rotation right now and I am teaching about angles and triangles. Geometry is a branch of mathematics that has a lot of vocabulary in it — and it can be tempting to start there: acute, obtuse, perpendicular. But students need understanding on which to hang all of these new words…otherwise they are simply "words, words, words" with no matter in them (apologies to Hamlet.)

To begin with, the concept of an angle is pretty abstract. Measurement for most kids still relates to lines. I can draw two identical angles (degree wise) but have longer rays on one than the other and students will almost always choose the one with the long lines as the "bigger" angle (even after I've tried to define degrees.) . They need experience to construct an understanding of what's being measured.

This year I found a great estimation game to give them that experience. Produced by NRICH, a math education program run by Cambridge University, the game gives you a target degree number, then an angle begins to open up wider and wider and you click on it when you think it's reached the target number. It's really fun — here's the link.

Very quickly, students began to get a real sense of what a 45 degree or 110 degree angle was. Next, I gave them a protractor and taught them how to use it to measure angles exactly — using their estimation skills to confirm their measurements. With a deeper understanding of what an angle was, students were able use the protractor more effectively — puzzling through where to put the center of the protractor, where to put the base, and which scale to read.

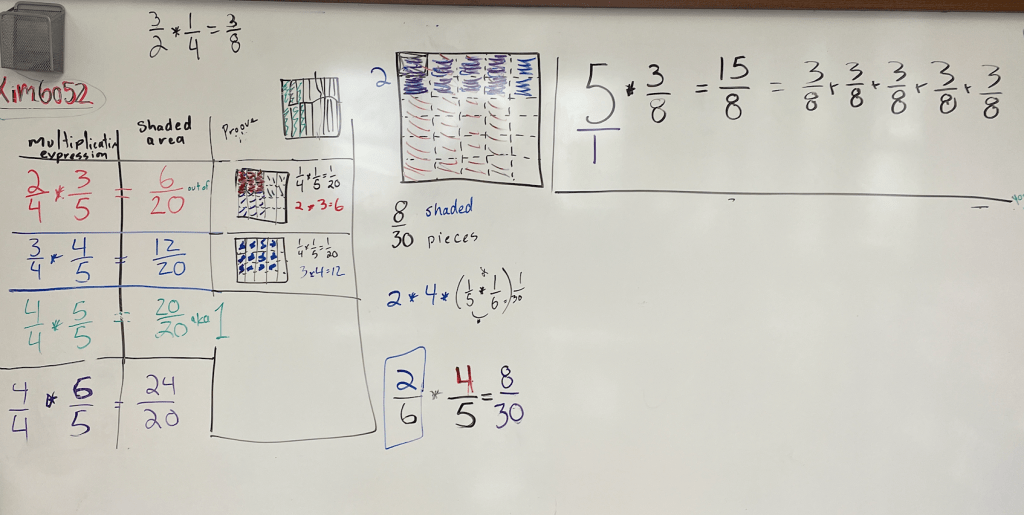

Using our new protractor skills, each child measured the angles in a unique triangle. The students found the sum of their triangle's angles and they were very surprised to discover that many had the same(ish) sum, even though we all had different triangles. How could this be? More than half the students felt that it might be a coincidence…I had just drawn 20 triangles that happened to do that.

And here is the crux of why it is so important that students make discoveries in math. So many times, we are taught something — "the sum of the interior angles of a triangle is 180 degrees" "to divide by a fraction, flip the second fraction and multiply by it instead" "if the bottom number is bigger, go next door, subtract one of those and put a little one next to the number in the column you're in."– and we dutifully memorize it. But we don't remember it for long or we don't believe in it enough to trust it when we are solving problems.

Kids must believe that math makes sense. They must push and ask until the concepts do make sense. Only then will their foundation be strong enough to build upon — otherwise, eventually, our brains run out of space to hold all of the memorized rules.

Faced with such a skeptical crowd, I cut out a triangle, tore the angles off and placed them together to show they made a straight angle (180o). There were audible gasps…and still skepticism. I asked again, "How many of you think that your triangle will do the same thing?" A few hands went up (if I had to guess, they were the hands of the kids whose sum was exactly 180o). But the rest of the class wasn't so sure. I wasn't surprised. When given the chance and encouraged, students really want to know why something happens. So I had them each try it with their own triangles. Drumroll…..everyone's triangle worked. All of our angles were a perfect sum of 180o .

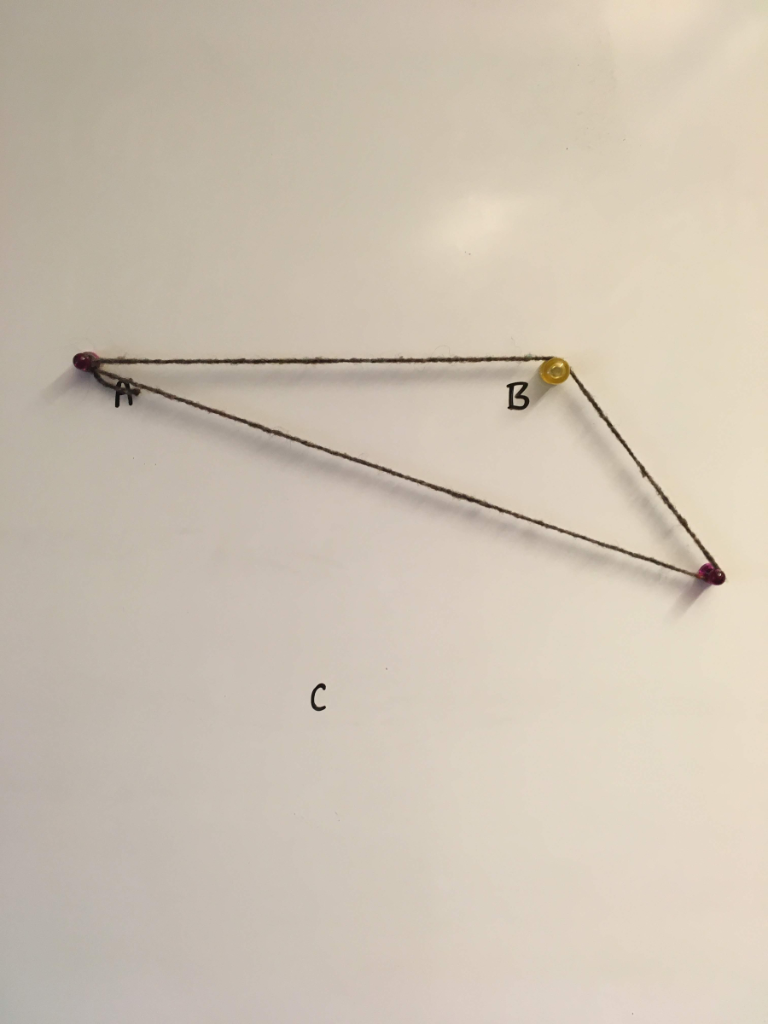

But why? I created a triangle on the white board out of magnets and a piece of string. I assigned half the class to observe Angle A (see below) and the other half to observe Angle B. While I moved the bottom point from side to side, I had the students say what was happening to their angle. Half said, "Bigger, bigger, bigger, bigger, bigger" while the other half said "smaller, smaller, smaller, smaller." We had shown that what one angle loses, the other gains. And to prove it…well, that will come back in a few years but these students will be ready.

Leave a comment