Fractions. Even for adults, the word can bring on a shudder. Often, we were taught mnemonics to help us remember things that weren't supposed to make sense: “If the bottom is bigger, the number is smaller,” “The big number goes on the bottom” or “Ours is not to wonder why, just invert and multiply.” These are counter intuitive at best and, at worst, incorrect. Often fractions were taught almost as a different subject – as though the rules of math didn’t apply. No wonder we shudder.

Fractions. Even for adults, the word can bring on a shudder. Often, we were taught mnemonics to help us remember things that weren't supposed to make sense: “If the bottom is bigger, the number is smaller,” “The big number goes on the bottom” or “Ours is not to wonder why, just invert and multiply.” These are counter intuitive at best and, at worst, incorrect. Often fractions were taught almost as a different subject – as though the rules of math didn’t apply. No wonder we shudder.

But fractional thinking is crucial in problem solving and comfort with fractions enables students to make rich connections among math concepts. For that reason, fractions make up a large portion of the fourth and fifth grade math standards (both Minnesota standards and the Common Core). What is the best way to teach them?

If only it were that easy. It turns out there is not one best way…we must approach the subject flexibly so that students create many levels of understanding.

Models

We use circles sometimes to represent fractions. But we also use bars and sets of objects. We use measuring cups and graduated cylinders. We return to the number line again and again to show where these numbers fit into the system that students are already familiar with.

We focus initially on fractions students have an intuitive sense of – halves, wholes and then thirds and quarters. These are our benchmark or landmark fractions. We come back to them again and again to compare numbers and to test out conjectures (will this always work?)

Then we use the model to expand into more abstract numbers – things we can’t draw like hundredths. Anchored in the concrete, students are able to extend their understanding to the abstract.

Tackling Misconceptions Head On

Asked which is bigger, 3/4 or zero, many students will initially say zero. By working with fractions on a number line, examining improper fractions and considering real world applications such as cooking, students can challenge that misconception and shift their understanding. But you can’t just tell students that proper fractions are bigger than zero and less than one, they have to discover it for themselves. They have to trust a concept before they will use it independently. My saying it is so doesn't make it so. Many times I think we’ve “got” something and when we return to it the next day, the concept is wobbly again. This kind of learning takes time.

Using Conjectures to Build Understanding

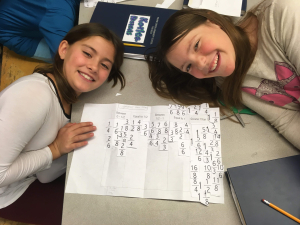

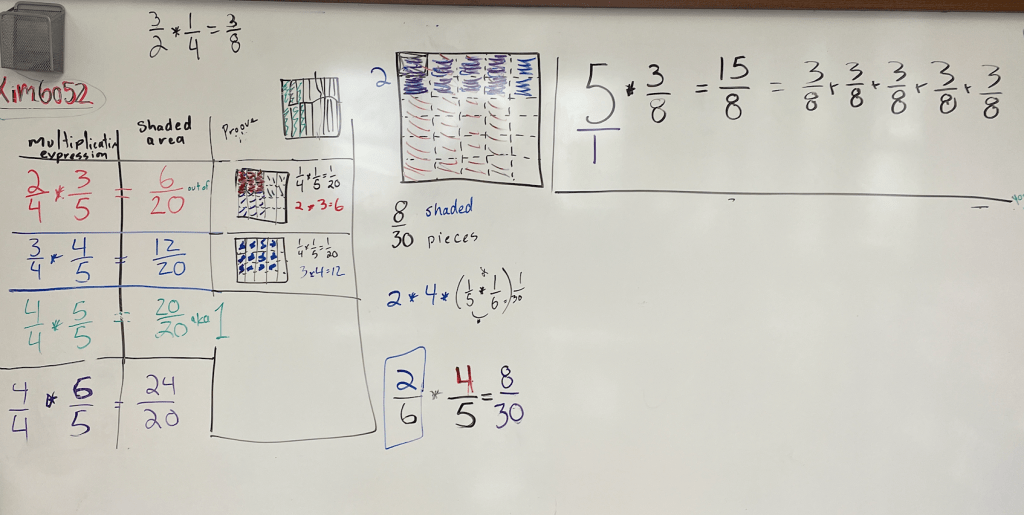

When adding fractions, students will often add the denominator as well as the numerator. When dividing by a fraction, students will often multiply (numbers are supposed to get smaller when you divide, right?!). This past week I did a series of number talks around dividing by a fraction. In previous number talks, these students had realized that to multiply fractions you could multiply the numerators and the denominators. I didn’t just tell them this. We did several number talks multiplying a whole number by a fraction to see what happened and why. We then transferred that understanding of what multiplying by a fraction was doing to multiplying two fractions. We began with fractions that students could visualize – some students noticed that the answers could be obtained by multiplying numerators and denominators. Did this always work? Yes. Why? The students worked to understand the mechanics. Once we were assured that it always worked, we dubbed it “The Sam Method” for the child who initially proposed it (even though it is the standard US algorithm.)

When adding fractions, students will often add the denominator as well as the numerator. When dividing by a fraction, students will often multiply (numbers are supposed to get smaller when you divide, right?!). This past week I did a series of number talks around dividing by a fraction. In previous number talks, these students had realized that to multiply fractions you could multiply the numerators and the denominators. I didn’t just tell them this. We did several number talks multiplying a whole number by a fraction to see what happened and why. We then transferred that understanding of what multiplying by a fraction was doing to multiplying two fractions. We began with fractions that students could visualize – some students noticed that the answers could be obtained by multiplying numerators and denominators. Did this always work? Yes. Why? The students worked to understand the mechanics. Once we were assured that it always worked, we dubbed it “The Sam Method” for the child who initially proposed it (even though it is the standard US algorithm.)

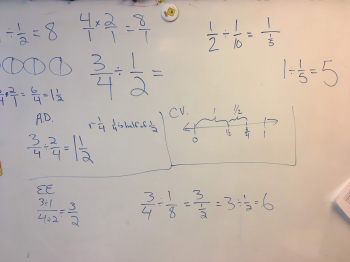

Then we went on to tackle dividing by a fraction. We started with whole number dividends again, using familiar fractions and analyzing what it means to divide. 6 ÷ ½ for example could mean “how many halves are in 6” just like 6÷2 could be interpreted as “how many twos in six” Armed with that knowledge, students can construct an answer.

This past Friday, we considered this problem ¾ ÷ 1/2. Again, we could logic it out (there are 1 ½ halves in ¾). Some students created models in their head to figure it out. One child said “I used the Sam method…and got 3/2 but was that just a coincidence?” Hmmmm…could you just divide the numerators and then divide the denominators? It was not an algorithm I had ever used (I multiply by the reciprocal when I divide by a fraction) and my first instinct was that it wouldn’t work…but then we worked it out thus:

3÷1 = 3. 4÷2= 2 You get the answer 3/2 (which is correct.). We chose another example and gave it a try. ¾ ÷ 1/8 We knew the answer was six (because there are two eights in a fourth. Now to apply the “Sam method.” 3÷1 is still 3. 4÷8 is ½. That leaves us with 3/ ½ . The kids were stuck. What does that mean? Then one remembered, “Wait, a fraction is division so we could divide again…3÷ ½ “ The group chorused, “Six! It works!” (There are six halves in three).

The Power of “Basic” Facts

The Power of “Basic” Facts

Knowing one’s multiplication facts can unlock the mystery of fractions for many kids. I was working with my exploration math group to discover equivalent fractions. First we used a fraction wall – a model that shows stacked bars divided into halves, thirds, fourths etc. Equivalent fractions share a vertical line in the wall.

We looked at all of the equivalent fractions that we found for a third. What did all of these fractions have in common? The students who knew their multiplication facts right away saw that all of the denominators “were threes” others saw “you can skip count by threes to them.” This relationship was much harder to recognize for the kids who didn’t yet know their facts. It seemed somewhat arbitrary that all of these fractions were equivalent. They could see it on the fraction wall but they couldn’t extend the concept beyond the fractions modeled in the picture. The kids who did have more familiarity with their “3 facts” could start to formulate a method to find equivalent fractions.

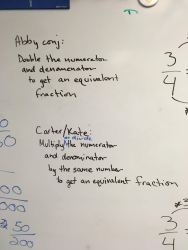

One child suggested that you could get an equivalent fraction by doubling the numerator and denominator. We tried it out on the fraction wall and then using numbers they were familiar with…yes, the conjecture was true.

Two more students suggested that you could also triple or quadruple each number…it didn’t matter how much bigger you made it as long as you did the same thing to the numerator and denominator. We tested that out, too, with a fraction we felt comfortable with – one half. Sure enough it worked.

A third child asked if it would work with division. This was a little trickier to imagine with a model. I suggested that it would be like gluing pieces together so 4/6 divided by two would become 2/3 because we would group (glue) two pieces together. Did division work? We checked out a few more examples and concluded that, yes, it did work, as long as you divided the numerator and denominator by the same number.

Students with basic fact fluency saw the relationships much more easily and were less confused than students who didn’t have their facts. It might be compared to color blindness – the person next to you is seeing something clearly that you can’t see at all. With support, everyone can see it…but students without their facts are slow to see the relationship independently and use it in novel situations.

Experience Counts

The more context students have for fractions, decimals and percentages, the better. They can lean on their number sense and instinct to make sense of the abstract, number only representations of fractions. Why don’t you add denominators when you are adding like fractions…well, would putting three quarter cups in your recipe give you three twelfths of a cup? No, you’d have three quarters. Knowing that…feeling that, can help students make sense of the algorithm for adding fractions when they are ready for it.

Fractions need not be confusing and mysterious. When children have the time and experience to discover fraction relationships everything can fit together.

Leave a comment