Theme. It’s something so woven into the essence of Prairie Creek and the Herons that I often forget that it’s not part of every classroom everywhere. Theme is our engine. It propels us. It teaches us how to ask questions and make conjectures. We learn to collect evidence and seek a variety of perspectives. Theme is not as easy to define as “science” or “social studies” — it’s these things, absolutely, but it’s also literacy, writing, communications, social and emotional learning, math and critical thinking. Without theme, I wouldn’t still be in the classroom — it’s that compelling a way to teach.

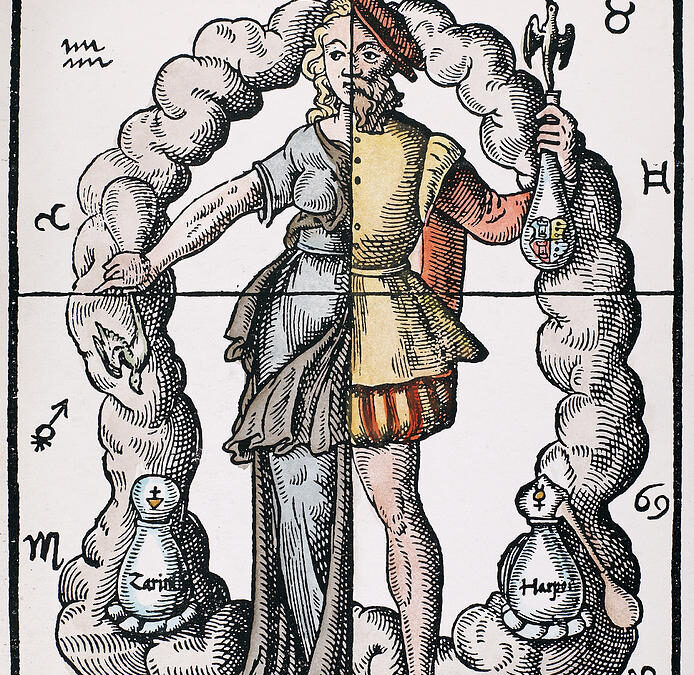

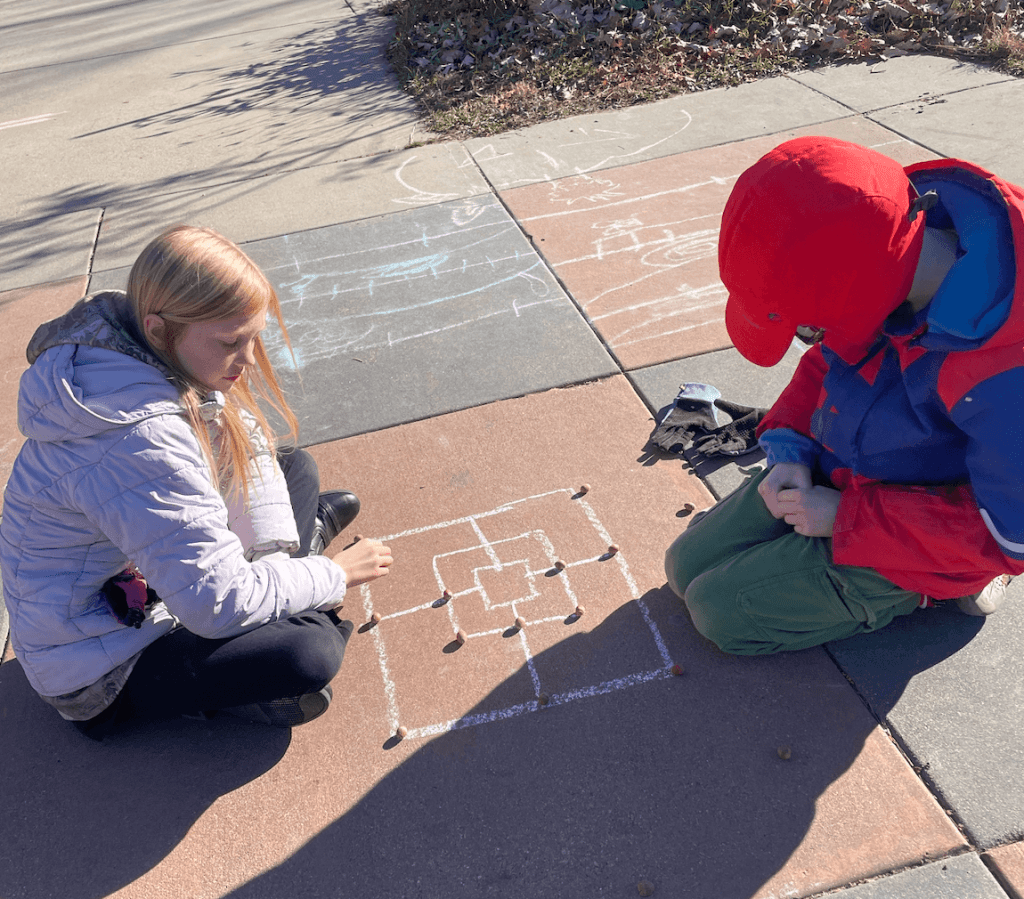

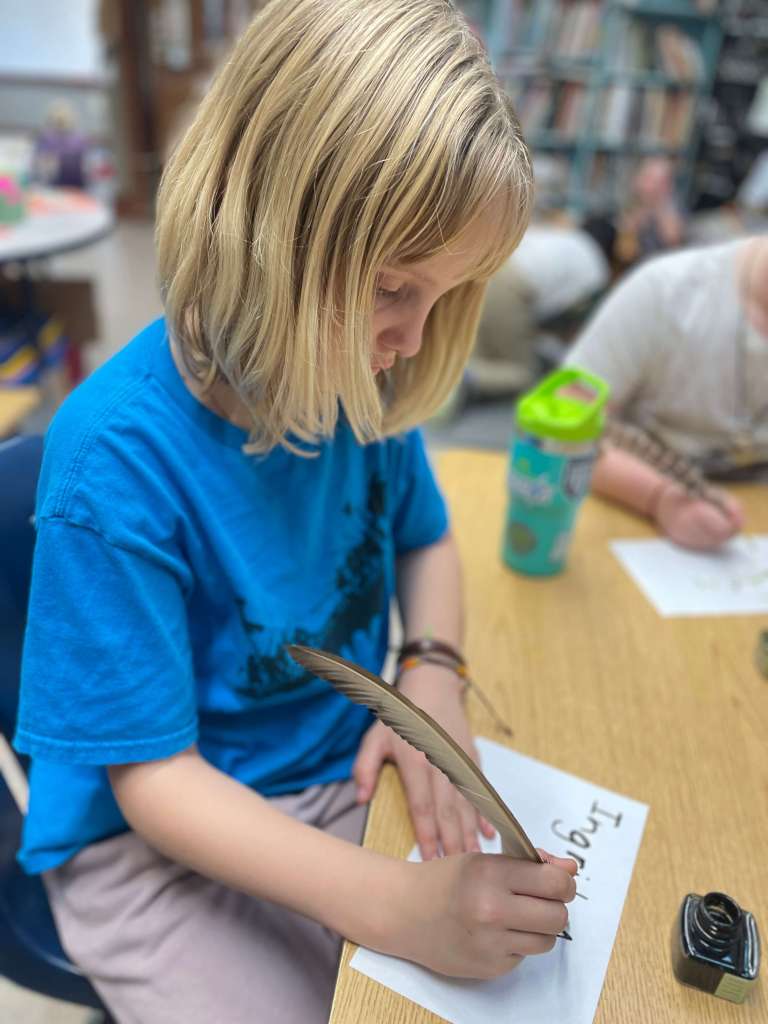

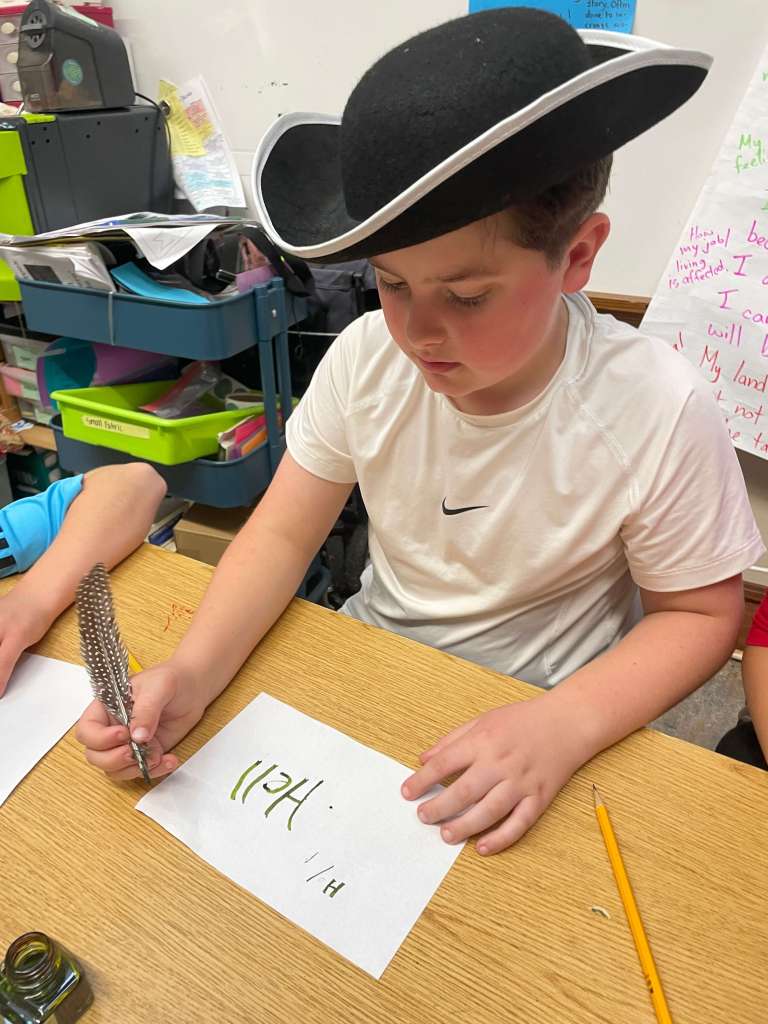

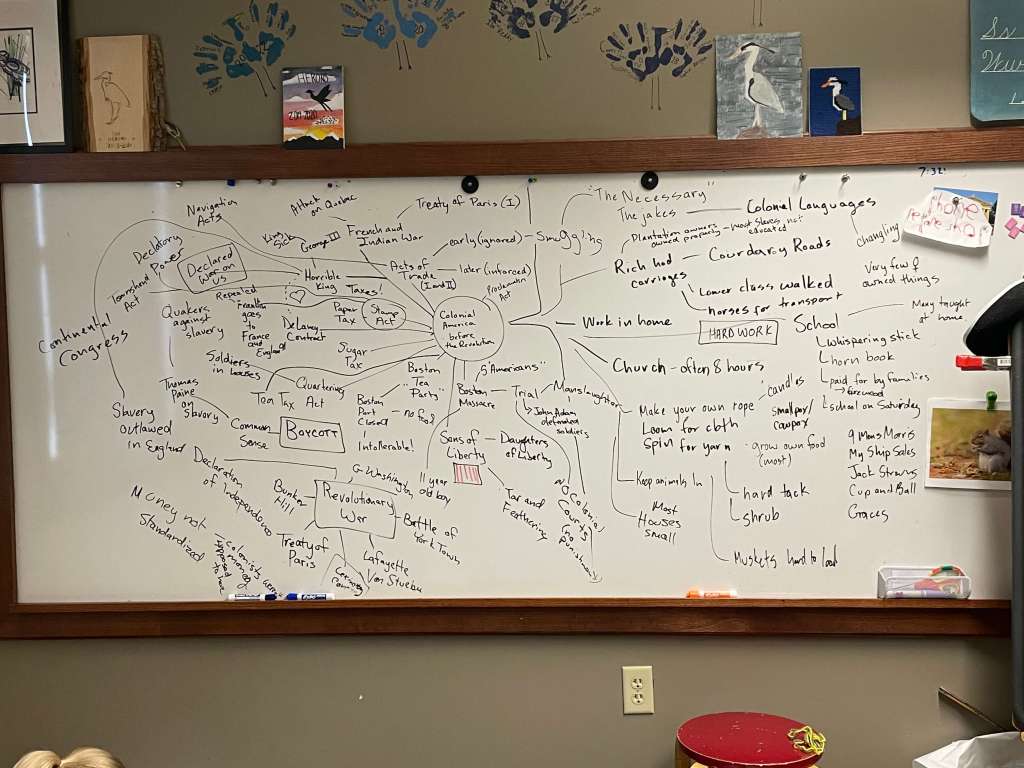

Our current theme is about pre-revolutionary America. We’ve spent about ten weeks immersing ourselves in the world of the British colonies from 1750 to 1776. What people were there? What was important to them? How did they live? What were their struggles? Their motivations? Their beliefs? We learned about the physical reality of life — what shrub tasted like, how to make candles, how to write with a quill.

We also examined the myriad perspectives and experiences of the people in the colonies. Through role play, we considered the impact of class, religion and occupation on people’s experiences with the laws and government. We looked at the experiences of indigenous people and enslaved people and the impact of those groups on the colonies (and the impact of the colonizers on those groups.)

At the beginning of this week, we filled the white board with what we had learned. As soon as one student said something, there would be a chorus of “Oh yeahs!” and then new hands would shoot up. This is a sneaky way to review everything that we learned – culminations offer the best way to solidify new learning that I can think of. Students are eager to remember everything we’ve done because they want to make sure they don’t forget anything they might want to teach.

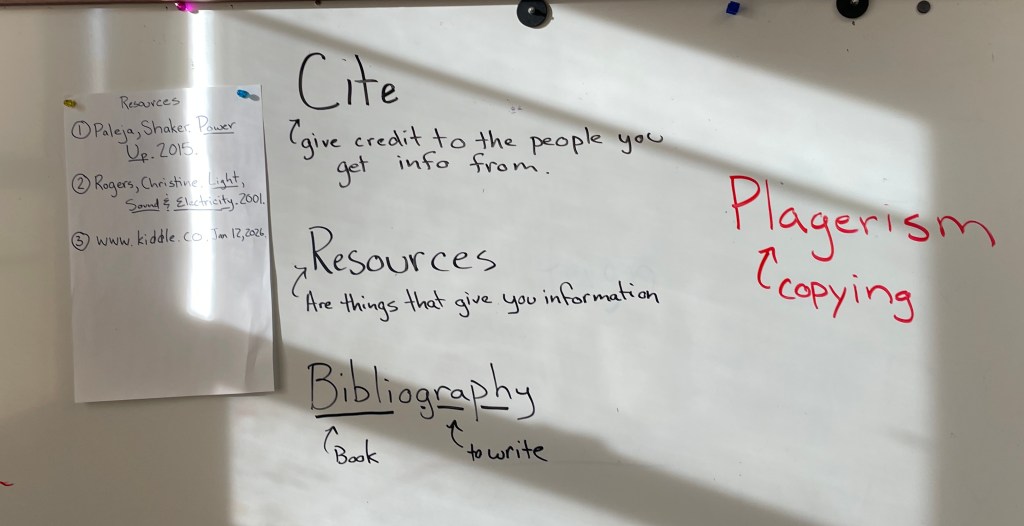

On Tuesday, we began the most important part of a theme – how will we teach what we’ve learned? It is through teaching that we truly understand something. Students will have to move from “getting it” in a vague way to being able to articulate it and explain it. Often, to help someone understand, they’ll have to know the content below the surface, too. Students identify the information they want every person who visits their area to learn. They develop ways to teach that information through doing, listening, reading and looking. Then they go about making what they’ll need to teach – activities, talking points, visuals, dioramas — it’s up to them to figure out the mode that will work best. It’s very common for students to realize that they want or need to know more — they head back to our print and on-line resources on the hunt for answers to specific questions. After all, as a teacher, they never know what their students might want to know more about.

After our first day of work, many groups were making scripts of what they wanted to say to each visitor. “Hi, I’m _______ and I’m teaching about ______________.” This felt very safe to them and, as I reflected on it, matched how videos impart information A->B->C->D->E. This linear approach reminds me of the old AAA Triptic where you would share your destination with AAA and they would compile a book in which each page was a piece of highway you would travel on (Google Maps does the same thing but without as much paper).* It’s efficient…but you miss all of the side trips you can take. It’s also not an exciting way to learn as an audience.

I called everyone together and showed them two different ways to think of information. One was linear, the other was planar. To extend the map analogy, a planar map shows a birds eye view of an area. You can use it to go from A->B->C but you can also use it to get to C right from A then head over to E before looping to B. I modeled the difference when it came to teaching. I had someone come up and I presented all of the information I had then asked if they had any questions. (They didn’t).

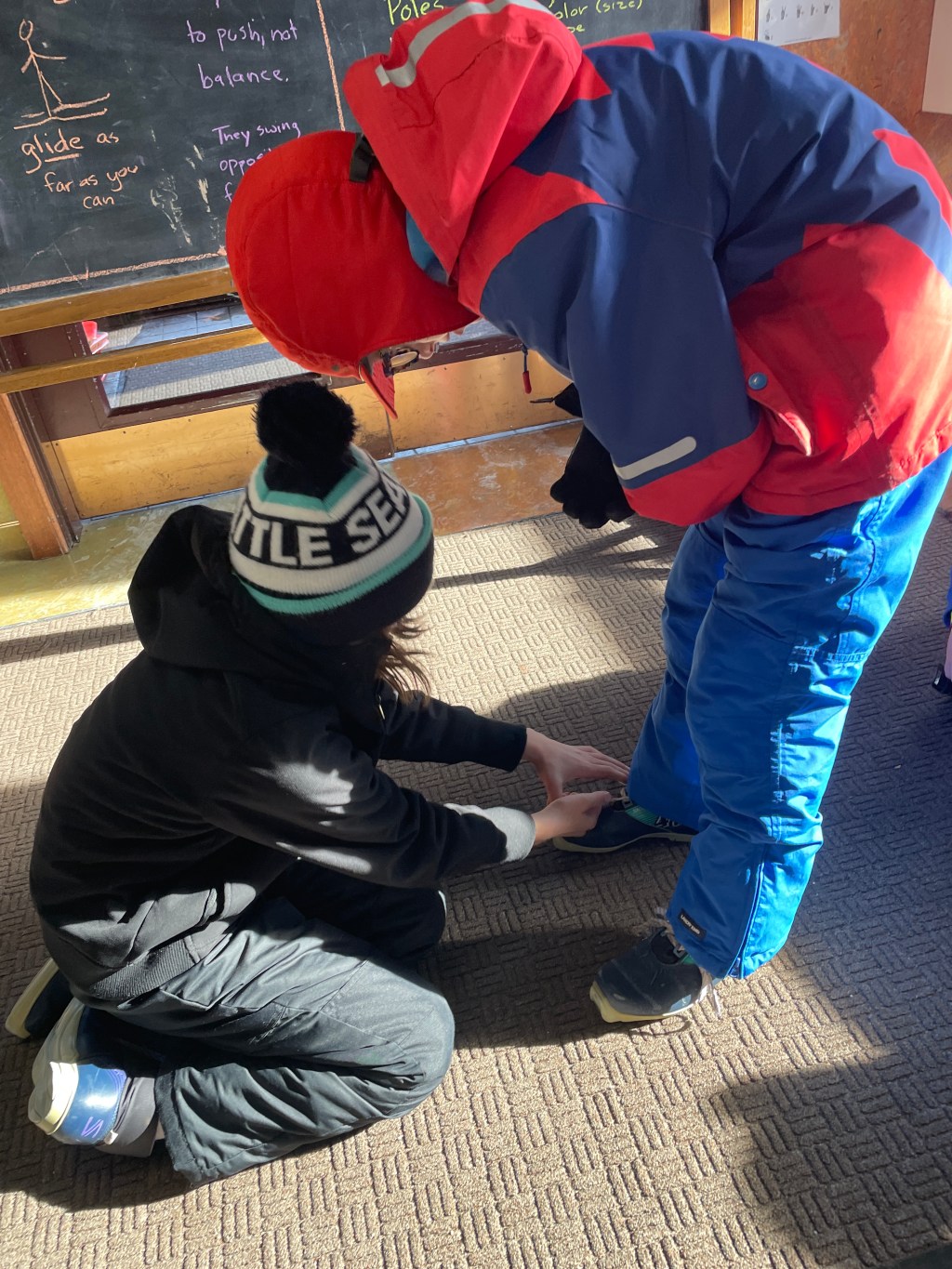

Next I invited them to look at my table on which I had a jar of leeches (pretend), a chart of the four humors, some willow bark and a notice for the smallpox inoculation. I put my hand to their forehead and announced that they might have a fever — which one of these would be helpful? That lead to a discussion of what the other things on the table were. “Why would you use leeches?” “Well, if your humors were out of balance, I might have to remove some of your blood?” “Humors? what are those?” Soon, we were having a conversation about medicine in the 1700s.

They all agreed — it was a lot more interesting to learn like this. It also required more flexibility (and work) for them as teachers. What was their “hook” going to be? What were the various directions that the conversation might go? How could they prepare to teach an array of topics?

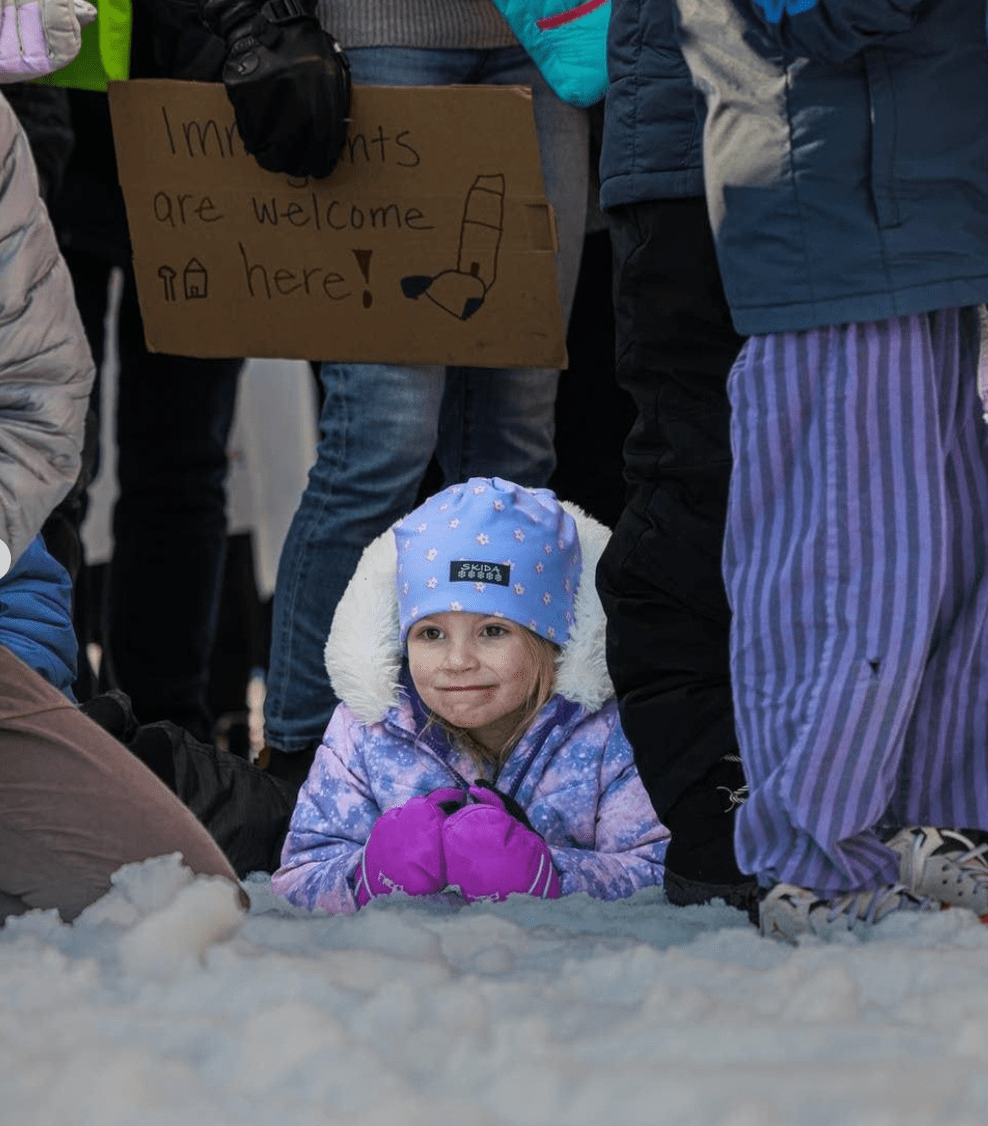

It also requires a bit more work from the learner (which is where you come in!) When you come to our culmination next Thursday (12:30-2:00) explore and ask questions of curiosity. Questions of curiosity start with noticing something that the children have created for their area and asking about it (note that they are different from “gotcha” questions.) The students are nervous about sharing information this way, a script feels more secure, to be sure. But they know their stuff and, if you happen to ask a question that they don’t know the answer to, perhaps you can hypothesize together.

We’ll work furiously for the next week so that next Thursday we’ll be ready to welcome our guests to the eighteenth century where they will learn from us about the challenges and decisions that faced the people living in the British colonies in the late 1700s. We can’t wait to teach you!

Leave a comment