Thanks to our school's wonderful Catalyst Grant*, five other teachers and I spent the last part of spring break on a retreat up North. While there, we took a class on spoon carving at North House Folk School.

Thanks to our school's wonderful Catalyst Grant*, five other teachers and I spent the last part of spring break on a retreat up North. While there, we took a class on spoon carving at North House Folk School.

"Spoon carving?" you may well be asking, "Why?!" Well, none of us knew anything about spoon carving. Often when we talk about learning new things at school, we use a five point scale:

- You don't know you don't know.

- You know you don't know.(often feels embarrassing but is part of learning)

- Awkward practice (a frustrating but necessary step in learning something)

- Proud competence (showing off)

- You don't remember not knowing.

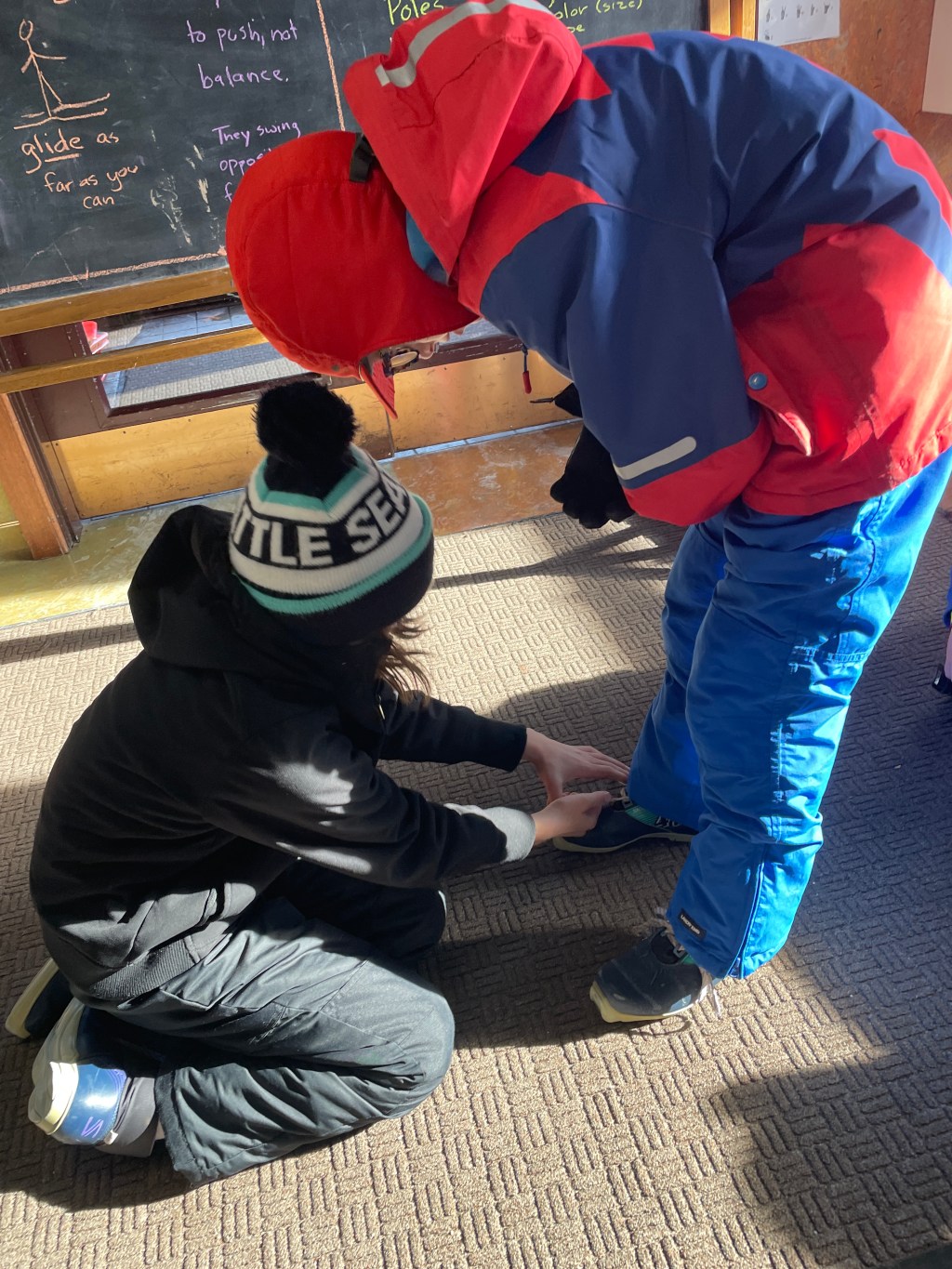

As an adult, when was the last time you realized you knew absolutely nothing about a topic? When did you last try something that made you feel uncomfortably incompetent? As teachers we ask our students to do this multiple times a day. So we felt like it would be a good idea to remember, really remember, what it feels like to try a completely new and awkward skill.

When the instructor brought out an axe and a log we all looked at him in disbelief. I asked a lot of  questions and, when it came time to use the froe to split the log, I raised my hand quickly to give it a try. And then I failed. It had looked so easy when Mike did it: a quick flick of the wrist brought the mallet down on the wedge and the wood split. No problem. But with no amount of pounding could I so much as dent the top of the log. My colleagues shouted encouragements and I tried my best not to glower at them. I really, really didn't like this. I hunkered down and tried this angle and that. And then, with difficulty, I surrendered the tool to another classmate who with a few strikes of the mallet halved the log.

questions and, when it came time to use the froe to split the log, I raised my hand quickly to give it a try. And then I failed. It had looked so easy when Mike did it: a quick flick of the wrist brought the mallet down on the wedge and the wood split. No problem. But with no amount of pounding could I so much as dent the top of the log. My colleagues shouted encouragements and I tried my best not to glower at them. I really, really didn't like this. I hunkered down and tried this angle and that. And then, with difficulty, I surrendered the tool to another classmate who with a few strikes of the mallet halved the log.

How many times had this very drama played out in my classroom? When an expert does something, it always looks easy. And then, as you make your own independent attempt, nothing makes sense anymore. Nobody likes the feeling of not getting it. It takes a lot of courage to try repeatedly or to not compare oneself to others but "go at your own pace." Sometimes that awkward practice is done in a very public place — your struggle is evident and it takes a lot to not dismiss your work with self-depricating humor or excuses. It takes a lot not to turn away and think, "This just isn't my thing."

Hours and hours and hours later I had hacked and gouged and whittled a spoon out of that log. It was hard work physically at times but, mostly, it was mentally hard to be really bad at something. And yes, I know it should all be about the process but gee whiz, I wanted a beautiful spoon at the end and what I have is an object in which I can see every glaring flaw. I know that if I make another spoon it will be easier. And, the one after that would be easier still. And, eventually, I might make a beautiful spoon.

But such competence comes only with much hard work — how amazing that our children are willing to take on this Herculean task of learning every day.

*The Catalyst Grant was begun several years ago at Prairie Creek. Teachers can propose and get funding for creative professional development. In the past, teachers have used the funds to study spanish abroad, take guitar lessons or learn to make books. To me, it's one of the ways Prairie Creek stays true to its progressive mission and the idea of life long learning.

Leave a reply to Nancy Willasmama Cancel reply